In my guise as a storyteller, I’ve recently started working to develop retellings of several longer tales. One of the themes that caught my interest, when I began thinking about doing this, is that of the Loathly Lady. While her best known appearance is within Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, in the Wife of Bath’s tale, there are plenty of variations (as so often with folk tales) and she turns up in Irish and Norse stories too. There’s rather too much material there for one blog post, so if any reader wants to uncover a little more more about those stories, there’s always https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loathly_lady

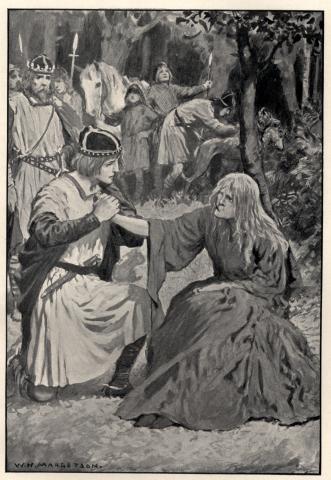

Original illustration by: W. H. Margetson

The version I’ve chosen to work with, for now, is one from the Arthurian cycle of stories, and it is centred on the character of Gwalchmai, originally regarded as the best of Arthur’s companions. Later renamed as Gawain, Gwalchmai eventually lost much of his prominence as the Arthurian cycle was increasingly Christianised and the likes of Lancelot and Galahad came more to the fore in the later romances.

It has always seemed, to me, important that storytellers should dig beneath the surface of the material they work with. I’ve been focused on Gwalchmai’s encounter with the Loathly Lady, but that isn’t to dismiss the other versions, as any living tradition evolves and draws into itself new threads, new streams of wisdom. But it can be all too easy to lose sight of the point in one story by trying to generalise from all its iterations. Hence I’m going to concentrate on just the one I’ve been studying directly, here.

Gwalchmai’s name, to begin with. It has been translated as meaning “The Hawk of May”. It’s a name that reinforces his role as, first and foremost, a warrior – in fact, in the earlier versions of the Arthurian cycle he is the pre-eminent warrior of the Round Table – and also reflects that he is in the service of the Goddess in her most overtly sexual form as the May Queen. Not surprisingly, the image usually associated with Gwalchmai’s shield is a pentagram, the five-pointed star of the Elements.

The image of the warrior has become profoundly confused, even distorted, within our society, to the degree that many people not only neglect it but have rejected it outright. But what does Gwalchmai tell us about the warrior’s true nature? He is a defender of the community, an upholder of justice, a figure of compassion and integrity; not, by any measure, an aggressive thug.

Neither is he a soldier, as such. Soldiers are generally taught to stand in ranks, obey orders without question, in effect to act largely as military automata. Genuine warriors, on the other hand and at least as an ideal, train to think and act independently, to understand the brutal and terrible realities of conflict and thus to value peace, to live by the values they uphold, to be protectors rather than invaders.

This story of Gwalchmai, the archetypal warrior, and his relationship with the Loathly Lady – an aspect of the Green Lady – tells us something more. It is that the warrior is intimately connected to the Goddess, most especially in her role as challenger and agent of change. This runs directly counter to the common assumption that deities related to the warrior’s role (like, as the assumption goes, the gender of all warriors) must necessarily be masculine. The Divine Feminine also has its fierce, combative, side. The best known Goddess in this regard is probably the Morrigan, the fearsome Washer at the Ford, a Celtic deity associated with war, death and transformation. Along with Her are Her various crow-sisters, such as Babd. But the association is one that crosses the apparent boundaries of culture and even time. Ishtar, in Babylon, was a Goddess of war as well as of sexual love; a dual role that reveals much about the relationship between those two dangerous, raw powers, and perhaps much also about the nature of the Loathly Lady.

The Lady is in fact another face of She who sets tests, who sets us off on the Path, and thereby both creates and initiates the circumstances and conditions that lead to growth. “That which does not kill us, makes us stronger”, is a quotation from Nietzsche, but it might equally have come from the twisted lips of the Loathly Lady.

The presence of the Lady is a relatively common occurrence in both Celtic myth and mediaeval story. In early Irish context, for instance in The Adventures of the Sons of Eochaid Mugmedon, She infers the rights and duties of kingship upon Her chosen male partner in the hieros gamos (sacred marriage), so showing Herself to be the presiding spirit of sovereignty itself. Later, She is closely woven into the tapestry of Arthurian story, appearing not just as an initiator for Gwalchmai but for Peredur as well.

The connection with sovereignty leads to a further thought. When Arthur himself first encounters the Loathly Lady in the wildwood, She is seated between two trees, an oak and a holly. In Celtic tradition, those particular trees are associated with Light and Darkness, respectively. It is the Oak King who holds sway over the lighter half of the year, the Holly King who rules the winter months. It is possible that the Loathly Lady’s chosen spot between the two indicates her fundamental ambiguity. But it also brings to mind the image of the High Priestess in the Tarot trumps, seated in between the black and silver pillars – the negative and positive poles – of the temple. It is a position of balanced power, suggestive of the capacity to work with both forces. Between the light and the dark; between love and war.

The implication is that to develop either aspect fully, it is essential to develop the other as well. The warrior must also be a lover, and vice versa. As my first Japanese kenjutsu teacher used to put it (none too subtly!), “Ten thousand cuts in the dojo and ten thousand thrusts in the bedroom make a person of character”. Or, “If you grow too big on just one side, you fall over”. The relationship between the two aspects could be considered to be dialectical.

Who is it, though, that Gwalchmai must do battle with? It is Arthur, in this story, who fights (and loses!) against a giant. There is no physical combat with the Loathly Lady, who is Gwalchmai’s challenger. No, Gwalchmai must wrestle with himself, with his own character. Some degree of understanding this has been preserved in the Japanese martial arts, though I might argue that it’s become largely misunderstood as the more modern and popularised versions of those arts have abandoned the realities of combat, emphasising instead the rules and expediencies of sport. However, the point remains that the warrior finds merely opponents and challenges in the outer world; the warrior’s great enemy is within.

How does all this relate directly to our relationship with the Land? How does the archetypal role of the warrior belong in a modern Paganism that, quite rightly in the context of our present society, emphasises the need for peace and healing?

As I sit writing this, the largest remaining significant green space in my home area is under serious threat from developers, who wish to turn it into a massive housing estate. I can immediately think of three important sacred sites affected by road-building and even quarrying. Climate change is already altering our world in unpredictable and devastating ways. We live in a society in which everything – resources, people, the earth itself – is reduced to a commodity, into something that is there to be bought and sold, exploited and discarded.

In such a world, there is a growing need for warriors who serve in the spirit of the ancient deities; warriors who are informed, articulate, and activist; warriors who know how to love and how to heal as well as how to fight in a just cause. But, fundamentally, the journey to that warriorhood emerges from within…